[00:00:00] Speaker A: You're tuning into salon era, a series from lady lis that brings together musicians from around the world to share music, stories and scholarship with a global audience of early music lovers. I'm your host, Deborah Nagy, and this episode, phoenix of Mexico, was originally premiered in fall of 2021, and it has always been one of our favorites. This fascinating episode centers on Sorjuana Ines de la Cruz, dubbed the Phoenix of Mexico. A brilliant writer, philosopher, composer, poet and nun in 17th century Mexico, Sorjuana wrote for many patrons, but her epic poem Primero Sueno was written for herself alone as a true expression of her ambitious vision.

Guided and inspired by Sorjuana's poem, this episode brought together bassoonist Catalina Guevara, viques Klein, violinist Karin Cuela Rendon, and mesa soprano Raquel Winneck Young with Les de lis musicians to celebrate her legacy.

Sorjuana was mainly self educated. As a young person, she worked her way through her grandfather's extensive personal library. She wrote prolifically in Latin, Spanish, and najuatl, and she gathered together intellectual elites in her own personal salon within the convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronamite order in Mexico City.

Sorjuana's insatiable intellectual appetite also made her an outspoken advocate for women's personal, intellectual and religious independence. She was a feminist way ahead of her time. Known by many names, including the 10th muse and the Phoenix of Mexico, Sarjuana inspired intellectuals and composers well beyond her circle, as her writings, which included poetry, dramas, philosophy and music, traveled throughout Latin and South America as well as to Europe.

Championed by mexican writer Octavio Pass in the 20th century, Sorjuana became a national symbol in Mexico as a woman, writer, and religious authority, even appearing on Mexico's 200 peso bill.

Soruana's epic poem Primerosueno is a philosophical and descriptive silva that explores the subconscious, the conscious, and the thirst for knowledge.

In this episode, the conversation and musical performances trace the poem's architecture as we celebrate its author's musical, spiritual, and intellectual legacy.

We'll begin as primro suenhodes, with the dream, which subsequently inspires contemplation, where we'll consider Saurjuana's quest for knowledge and her engagement with science and theory. We'll then explore being, including Soruana's humanity and relationships before returning to consciousness or awakening, where it is revealed that Sorhuana herself is both the author and the subject of the poem.

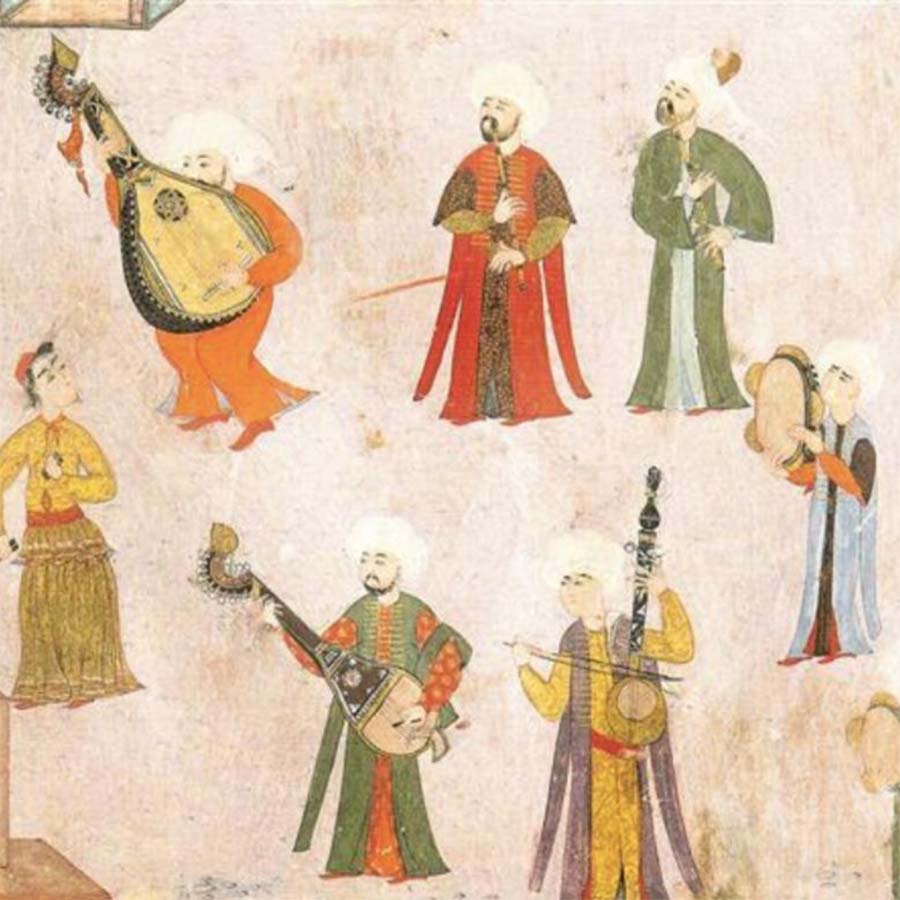

All the music you'll hear was recorded specifically for this episode. We'll hear the single confirmed composition by Sorhuana herself, as well as works by guatemalan composer Rafael Castellanos, bolivian composer Andres Flores, and andean composer Antonio Durandela Mota.

As much of this music is not readily available, we remain indebted to Bernardo Ilari, professor of music at University of North Texas, for sharing his knowledge and scores with us. Musical arrangements were created by Catalina and Alex Klein and ten musicians from across the western hemisphere, representing Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Chile, Panama. The US and Canada came together to create these performances. A special welcome to our featured guests for Phoenix of Mexico, Metzo, soprano Raquel Winneck Young in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Catalina Guevara Klein in Calgary, Alberta and Karin Cuelarendon in Montreal, Quebec.

[00:04:08] Speaker B: Thank you so much for joining me tonight. It is great to have you here and to be able to talk about Sorjuana.

[00:04:15] Speaker C: We are also glad to be here. Deborah, thank you so much for putting this episode together and for putting us all together.

[00:04:22] Speaker B: Indeed.

[00:04:22] Speaker D: Yeah.

[00:04:23] Speaker B: I love the way that Nira has the potential to bring us together sometimes for the first time, to talk about our passions. And I know that you all have a shared passion in Sorjuana, and it was you, Catalina, who actually proposed the topic for this episode. And so for each of you. But maybe starting with Catalina, what was your first encounter with Sorjuana, and what is it about her life and work that resonates with you?

[00:04:52] Speaker E: Well, for me, so I was a teenager at the french school in Costa Rica, so I was 17, and as part of the literature class, we had to analyze poem by Natalacruz. At that moment, the poetry of Sorojuana was a calling for my intellect. It was something else, like her way of putting words together and her rhetoric and all her creativity was something new to me. And Sorojuana remained like, oh, this is a women of genius and I want to remember these persons forever. What part of her life resonates with me? Well, her desire to learn. Sorhuana was always looking for knowledge everywhere, and the way she connected information to create more knowledge and to create more content, that is the part of her that resonates with me. So religion and wisdom were together for her, but she also cared about science, mathematics, poetry, philosophy, music. So when I think about the 4000 books she recollected in her own library, well, in her desire to learn, that she was also advocating for all women to have access to more knowledge and education.

[00:06:14] Speaker B: And Karine, how about for you? What was your first encounter with Sorhuana and what resonates for you and her work.

[00:06:22] Speaker C: What actually fascinates me about Sorhuana is similar to what Katrina says is this drive, this forward looking mentality. By putting herself in a self prescribed position of authority, she was able to defend all women's rights to formal education in this way, serve as an intellectual authority through writing and publication.

By doing that, she was also able to transcend all these dominant historical forces of the conquest, the colonialism, inquisition, and patriarchy.

And that is just fascinating. It's this figure that lives with us all. And just like Catalina, my first encounter with her was when I was in school. In middle school?

Yes, through her famous poem, which you will hear later, Ombres Nessios, in which she's showing this very forward looking mentality, and she's already in the 17th century denouncing hypocrisy of men, patriarchy in their expectations of women. So, yeah, this was the part that fascinated me, how someone had the will to make herself be heard.

[00:07:45] Speaker B: I look forward to hearing the. At the end of our program. Raquel, finally, I have the same question for you, and you're so engaged, in particular recently, with texts and texts of golden age spanish writing. What was your first encounter with Sarjuana, and what about her work resonates with you?

[00:08:06] Speaker F: Well, my first encounter was my mother reciting poems for me at home, not knowing where they were coming from. And then I realized in school, like Catalina and Karen, this person exists. Sorjuana is very well known in Latin America and South America. So we studied her in school, in the. Was a movie in Argentina made about her.

And what resonates to me is the fact that she was true to herself. And like my friends here, her insatiable desire for knowledge, but also not only the knowledge of science, which, of course, was ahead of her time for her to go for it, but the understanding of the human soul, just her sensitivity and her brilliancy into the world. And then I re encountered her again recently when I started studying spanish linguistics and latin american linguistics and art.

[00:09:09] Speaker B: In a moment, we'll hear Madre de los primores, which is the one piece of music by Sorjuana that survives today in Guatemala cathedral archives. And at the opening of this piece, Raquel, you chose to recite some verses from Primero Sueno, and I wondered if you could just talk to us a little bit, telling us what this passage evokes in terms of images and how this piece relates in your mind, to the theme that we have tonight of Primero Sueno.

[00:09:38] Speaker F: Yes, certainly. So there are two reasons for me at the beginning of the poem. The part that we are not reciting is piramidal. She chooses words that are extremely slow and bring us into that space right before we fall asleep, in which only the creatures of the night are protecting us. Everything is silent and slow. And there is a huge connection with this beginning of Madre de los primores, right? It's pace, the slowness. We very slowly fall into that space that she takes us in the poem as well. And then there is another aspect of Primerosono. The moment we chose to recite is the one in which she talks about the first cause, the primera causa, which for her is the creation of all essence, the beginning of everything, and her love and devotion for God and religion. So this devotion is seen and heard in madre de los primores as well.

[00:10:50] Speaker B: Fantastic. Let's listen.

[00:10:54] Speaker F: Isegunomero dibo materiales tiposolos, senors exteriors de lasquerimanciones, interiores of the lama interncialis. Kecomo, sovan piramidal, bundal, sierra lambicios.

[00:11:15] Speaker D: Fijura.

[00:11:16] Speaker F: Trampreyaspira, sandripunto don directa tiradalinia, Fijiano, silpunferencia, kecotiana, finita toda sensia.

[00:12:12] Speaker D: Can see the SA for so it is tv jump, and he see others that he sees the voice for. So.

[00:15:41] Speaker B: Thank you, Raquel, for such a beautiful and impassioned performance.

[00:15:48] Speaker F: Thank you, thank you. Such an honor to be part of.

[00:15:51] Speaker B: All of this, you know, following the dream at the opening of Primero Sueno, we find ourselves somewhere between sleep and consciousness. And in a moment we'll hear puesmidios anaciro apenar by Castellanos. And I wondered what the images are in that piece that resonate with you in relation to Primerosueno.

[00:16:12] Speaker F: So, yes, as you mentioned, we were just about to fall asleep. And now, starting from verse 198, which is what we did for this next section, Juanines talks about this separation that happens between the body and the soul. And she calls it a cadaver with the soul. So we rehearse dying when we fall asleep. In poes medias, there is also a separation. There are two statements, two clear thoughts. God was born to live in sufferance. Let him be awake. But he is awake because of me. Let him sleep. So this constant pull and push is reflected in that part of the poem of Sorjuana. Because once again, who is capable of sleeping in this dream is rehearsing to die.

[00:17:13] Speaker B: So let's take a moment now and listen to Puezmidios and we get all of this tension between sleeping and wakefulness.

[00:17:30] Speaker D: Sake.

Second wave.

Second.

When you think on your morning she let your we don't give it up.

See that they can live it on. They can live it can live for me.

They can live for me.

I said I'll be so open.

No voice, not anywhere, no more than all my God, it's open as me I thought it on it open up, kill. So yeah, the sham you wish me the ocean. I see the second wishing brother.

Secondly, not second you more than this one. You think on your Jesus you'll get without giving up Jesus yet.

[00:21:56] Speaker B: Bravo, both of you, for a beautiful performance. Puerto.

Absolutely gorgeous. Primerosueno. It is amazing for me to read for the first time in translation and be confronted with so much imagery as well as kind of display of knowledge, which was not so unusual in a way as to establish legitimacy for any writer in early modern times. But it's sprinkled through with references to Homer, to greek mythology of all sorts, to referring to the pyramids of ancient Egypt, and symbols about eagles, and even reflecting on what was then kind of modern science and ideas about medicine and for humors and all of that. I wondered, Karin, if you might talk a little bit about what we know about Sorjuana's engagement with not just musical but also scientific writings.

[00:22:58] Speaker C: Sure, yeah.

Sorjuana was an avid learner since she was very small, right?

It is known that by age four she was already bilingual in Latin and Spanish, and she also mastered Nawato anastic language.

Something that I wanted to mention, since we are talking about the pursuit of knowledge, is that when she was 16 years old, she wanted to join a university, which it was a privilege only reserved for men. And allegedly, she asked her mom to dress herself as men, so then she could disguise herself as a male student to be able to attend university. But she know this goes to tell you how hungry for knowledge she was.

Already. Catalina mentioned that she possessed this vast library, but something that wasn't mentioned is that she taught herself before entering the convent with the library of her grandfather, and she decided to enter the convert to become a nun. So then not to have, and this is quoting from one of her letters, to have no fixed occupation, which might curtail my freedom to study, unquote. So this is someone that was putting knowledge above everything else. It's very difficult to really gasp how much she actually nurtured herself. So, yes, and from the remnants of her library then, that she had to give up at the end of her life. We know that she had access to neoplatonic hermetician writers like Thanasus, Kircher, and also other philosophers like Descartes and Gasendi. But something that is very interesting for me, more relevant maybe for us musicians, is her access to writings of music theoricians such as Lorenze, Mercsen, Salino. And, you know, we can actually see in her work, and if Madri Los Primores is one of her works, we can trace this to Cerone's writings. So then it's not surprising that with all this knowledge, besides all the science that she was learning and reading about, she decided to write a treatise, a musical treatise, which she titled El Caracol.

She combined both knowledge of math and science and music. And she proposed in this treatise that musical harmony should be conceived as spiral instead of a circle. She also intended to simplify music notation and solve the problems that pythagorean trune imposed.

You can see how this minor was working beyond what we can actually gasp right now. Well, unfortunately, these treaties got lost. But there are some of these excerpts of these treaties found in some of her romances, like, for example, despise destin marmiamore catalog as mp 21, and in other works during Biancicos in Loas, in which she talks about musical harmony, composition and questions about temperament. But it's quite interesting because at the end she refers to someone very known, which is Elvira Sola.

[00:26:25] Speaker B: Anyway, well, this eternal search for knowledge and this very ambitious type of acquisition of knowledge, just not in books, but in ideas, is something that really is important in Primerosueno. There's a point in the poem at which actually, this sense of kind of overreach is symbolized by actually the character of Icarus sort of flying too close to the sun and getting in trouble. And in the next section of Primerosueno, we've been talking about all this lofty stuff of the transcendence of the soul and pursuit of knowledge on this extraordinarily high level. In the next section, we talk about being and the kind of human and the human relationship. So I thought it was an opportunity, Catalina, in particular, if you could speak about Sorjuana's relationships here on earth, in particular, because going into the comment means that you are not going to marry well.

[00:27:26] Speaker E: Okay, so it's important to understand that Sarjuana celebrated women as the place of reason and knowledge, not necessarily passion. So this is really revolutionary sort of reason and knowledge, women. Okay, so the convent was good for her because there she could study, she could write, she can even teach at some point. So she had an understanding about biblical, philosophical, but also mythological sources. So to be human, for Serwana means to continue to learn and to celebrate knowledge as part of life and her relationships. It's important to understand that her father was an absent figure since the beginning. And the patronage of the visceroids and viscerain of New Spain helped her to maintain. So it was the convent. But also she got very famous on her milieu because she was so smart. And so she got protected, and she got protected by important women, Donna Leonora del Caretto and Maria Lisa Marieque de la re Gonzaga, for example. So this patronage was very important for her freedom, because freedom means she could continue to learn, she could continue to write, she could continue to create things. And at some point, she became very dangerous for the religious authorities once she established that human arts, philosophy, science, were necessary to understand theology and to understand the world as we know it. So those relationships at Sorwana, even when she was very young, it seems like she got some invitations to marriage, but she said no, because marriage will mean that, okay, she will have to abide somebody. And so religions was her way to be free. The convent was a protection, but she looked for that protection in other places, like the patronage and stuff.

[00:29:25] Speaker B: The next piece that we're going to hear is Diosi Joseph Apostan. This is by Antonio Duranda la Mota. It's a work that's preserved in sucre, in Bolivia, and it's aviancico for Christmas. And so I wondered, Raquel, if you could talk to us about why you chose it and how it relates to our theme.

[00:29:45] Speaker F: Yes, absolutely. So it relates to these two. Putting together points of being human is to be the hinge, to be in touch with the supreme, but also to be dust. So my connecting point was the fragment that starts in verse 652, where Sorjwana talks about the characteristics of being human. She establishes that we possess three souls combined.

That makes us this hinge, the bisagra, the hinge and connection with God. We possess the intellect and imagination, but at the same time we are dust, we are low creatures, and besides the five senses, we possess three faculties, memory, comprehension, and will. So dioce. Jose shows exactly this in a humorous way. Right? The godly and the earthly, the betting ideas between God and Jose about Mary. But at the end, there is no winner. Both substances are important and poignant.

[00:30:54] Speaker B: Wonderful. Let's listen to Dios.

[00:30:57] Speaker D: I, Joseph, to stay on your side you get all this morning I voice on gonna take it one day I thought what a day.

You want to know just Samuel, you know for the little for the give you wonderful wanna say I wanna make it, take it for me, for your kids, everybody wanna get over your soul all your Spotify, your son, your soul.

West and I went on Bom you.

[00:35:53] Speaker A: This is such an exciting time for Le Delis and salon era. Le Delis is in the midst of its 15th anniversary season and our fourth season of Salan era. The episode you're enjoying today, Phoenix of Mexico, was created during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in the fall of 2021. This episode is full of heart and passion, and the remotely produced musical collaborations were some of the most ambitious this series has attempted. Ten musicians from across the western hemisphere, representing Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Argentina, Chile, Panama, the US and Canada came together to create these performances.

Thanks so much for being a part of our global community of music lovers as a listener to Solan era. With your support, we can continue to collaborate with engaging artists from across the country and around the world.

You can support Salon era by subscribing to this podcast and by

[email protected] your donations make every episode possible. Thanks again for supporting De Lif and Solan era by listening and subscribing to this podcast. Now let's return to our conversation with Catalina, Raquel and Karin.

[00:37:11] Speaker B: Bravo. That is so very fun. As we arrive to the end of the journey of Primero Thueno, the final part of the poem you defined as awakening. And I wondered how the nature of the poetry changes.

[00:37:25] Speaker F: Raquel, so if we remember, at the beginning, everything was slow with Madre de los Plimores. And then now towards the end, the rhythm of the words moves fast.

It is very resonant. It talks about musical instruments such as posinas like curved and hollow, and brings in the birds and the trumpet like sounds.

There is a clear battle of the day coming to conquer over the night, and which retreats to the other end of the earth to make the other half fall asleep now. So that is the cycle that we chose. So that is how we understand this life, right?

So something very important at the end and very poignant to me is that she says the last words, the world illuminated the world enlightened and I awake and myself awake. So no one else than Sorjuana is the protagonist of this journey. That was primerosonia.

[00:38:34] Speaker B: I think we have your recitation of the final verses to share.

[00:38:41] Speaker F: Consecual fin la vista de lo caso el fujitibo paso yensumismo de speno recobrada escor sando la liiento laruina Elamita del globo dejado el sol de samparada segunda des rebel de termina mir secoronada mientras noestromisferio la dorada lustrava de sol ma deja ramosa keconlusiosa de ordain distributivo repartiendo alascosas v sibling sus colore siva irestituda lo santidos exteriors suoperacion kedando alus macierta el mundo illuminado igio de spierta.

[00:39:26] Speaker B: So the next piece that we're going to listen to is isa edificio celebre by Andres Flores, who's a bolivian composer writing in the first half of the 18th century, which is to say, I don't know, 50 or so years after the death of Sorjuana. So I wonder a few things about this viancico. Obviously, her poetry is still being set at this late date all throughout Latin and as well as South America. And so how would this music have been heard or what kind of context? How was it that her poetry is still being said to music, and how is it that this music survives for us to this day?

[00:40:06] Speaker C: Yes. So this genre that was used by Andres Flores de Villancico, is in a spanish genre. Andres Flores was a composer in the first half of the 19th century, but he belongs to a long tradition of spanish composers. Andres Flores is a creole composer born from spanish ancestors, and before him we had Juan de Rojo as the maestro de capilla in la plata. Andres Flores never got to be maestro de capilla, but he was a choir boy in Juan de Rojo's choir, so he learned from him this spanish tradition. So this genre, the villancico, is not just a Christmas carol, as we may think. It's a song of the village. That's what means villan or villiano Villancico. It was performed at any festivity of the office during the liturgical calendar year, with text from the village. That was the basis of this genre. So then, unders Flores estidificio celebrity, for example, is a villancico composed for this holy sacrament festivities. But we don't know much about the performance practice of villancicos. But what we know from the descriptions of Villancico performances tell us that there was no doubt, as the transformation of the congregation from being a part of the celebration of the mass to an audience member. So the Bilancicos would perform at the end of the service. And we know that, for example, in the iberian peninsula in Spain, Villancico audiences were rowdy and noisy, and reacted to all the villancicos and clapped. So we may expect that this also happened in the Americas and during the colony, in colonial territory. The circulation of music, the circulation of writings, was so fluent that I would dare to say that the writings of Soruana arrived to La Plata, arrived to Potoxi fairly after her death, or maybe during her lifetime. We know that the viceroy and vice Ryan of Mexico, city of Viceroyalty of New Spain, they were her patrons and they paid for the publishing of some of her works.

[00:42:23] Speaker B: Let's listen now to Andres Flores's este depicio celebre.

[00:42:31] Speaker D: Sa Jesus little boy I know you got me roll this I know you let boy I just want it to go.

Y'all is on the phone close the start of all get my heart is we don't get. Let's say I'm gonna be going out in the comfortable.

I want to present it all morning single circle boy I but y'all throw let it all gonna stay on you.

I don't and I don't want to.

You got me.

[00:47:51] Speaker E: So I wanted to add that it's clear that Sorjuana is teaching us how to decolonize with deficiency. Celebre is the great example of how we should decolonize, deficie celebre. We think that it could be a cathedral or the religious authority, but it's not. Edificio is her work, is her art, and she wants her voice to be listened from the Arctic to the Antarctic. That is what she's saying to us. So edificio is her poetry. So remember that I said that she wanted women to be connected to knowledge and reason, but she had a passion, and passion was poetry. And the way she connects all the words and makes is teaching us how to decolonize. And that's what I love from this.

[00:48:35] Speaker B: Music that's so fantastic. And a great transition, actually, to returning to some of these themes that we talked about at the very opening of Sirjuana as essentially sort of a proto feminist. And I'm reminded a little bit of another amazing woman writer from 200 and 5300 years earlier, Christine de Pizan, writing the city of ladies and advocating for knowledge and for kind of women's intellectual and emotional and financial independence. And so, Karim, you had offered to read to us from ombres necios ombres.

[00:49:09] Speaker C: Necios cacosais alamo her sinrason simverque soy la cacion de lomis mokai sikon ancia sinigual solicitaisode salmal combatiso resistencia iluevo congravidad de cisquelindas locisola de lehensia paracer quierrel de nuedo de vuestro paracer loco al Nino Capone el coco ilo Latino keres compression necia ayara la caboskais parapretendida taist yen la poses lucrative el mismaniel estejo isiente claro.com El Favorial destin tenes condition Igual Kehando Osio Strata Burlando Sioskierambien Opinion Isio Sadmite Eslivian Siempretang Nesio Sandais Keconde sigual nivel Awona Kulpais Porcrel yautra por fascil culpais puescomo ade sartem plaza la queuestromore pretende silakes in grato Fende Ilaques Fasil and father Macentrelen Fado Ipena Kestro Gusto Rafiere Bieng Ayala Kenoschiere Ikeja Emora Buena Damuestra Samantes buena qualmayor Culpatanido Emuna Pasionerada la quekai de rogada Wilke roga de Caido okual es mas de gulpar anquel kiramal aga la capega port la paga wilke pada portica puesparacos pantais de la cul paquettas keretlas Kualasa says poasetlas kuala buscai de had de solicitar ides puesco mas rason de la queos puerto rogad bien comuchas aramas pundo kelivia westra.

[00:51:52] Speaker B: I wondered if anyone had any last words. Before we hear our last piece about Sorohana's legacy and influence, I just would.

[00:52:03] Speaker F: Like to say that she has enlightened centuries and she just lived in Mexico. She entered the convent. She never left. She's buried there and regardless, all this world that she created that made it certainly a better place to live. And it's amazing how much now she is being revisited and now we understand more and more and she's better known all over the world.

[00:52:35] Speaker E: I also want to say that if Sorjuana was in love, she was in love with her freedom and she was in love with knowledge and at the end she gave up in a way that she set us free to all women. She wrote in her own blood I the worst of all. So she had to sacrifice her freedom at the very end. But she's also sending us a message to all women. The message is so powerful because we as women, we understand very well every time we hear I the worst powerful, powerful words.

[00:53:13] Speaker B: Our last song is fuego, fuego by Antonio Durandula Mota. And the message is, if we don't change the world, the temple will be in flames both inside and out, which I think is an important message for us all, whether 300 years ago or today.

Let's listen.

[00:53:40] Speaker D: You go get this if you get my sick all day so get can be both like nobody knows you must be inside wake up something I don't get six people, they'll see noise. Come on, she said Yamah City said you said you me it's an arm rock one no westrade so I can eat the top with one more love. Withdraw, withdraw if it's your way for this, no but I guess I'll shake it you like a way only you can be all you want to see and say no can you don't wake up something I don't think it all is don't it's a close body.

Love your macrame.

Bring a king sweet if it anything.

[00:58:46] Speaker A: Perform live in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, on Saturday, February 17 at 03:00 p.m. And recorded for release online in March, this 75 minutes concert and conversation brings together harpsocordist Mark Edwards and pianist Jor Biran to explore Bach's momentous work and consider the unique challenges and opportunities that Bach's music has for us all.

Our show will also include images from a rare first edition of the Goldberg Variation, an interview with renowned Bach scholar Michael Morrison, and a live video feed that enables everyone a close up view of the magic happening at the keyboard.

We're proud to collaborate with the Riemann Schneider Bach Institute at Baldwin Wallace University and piano Cleveland for this event.

If you're in northeast Ohio on Saturday, February 17, join us to listen and learn as our featured guests share gorgeous music and fascinating insights in a casual setting at the Heights Theater in Cleveland Heights. Admission is free and no reservation is required. Details

[email protected] composers and audiences have long been fascinated by the extraordinary musician Orpheus, his trip to the underworld, and the human foibles that ensure his story ends in tragedy.

Tune in on Monday, February 26, as we premiere Orpheus Revisited, featuring beautifully recorded performances of music by Ramo Corbois and Jonathan Woody from Ley de Lisa's digital catalog. Paired with fresh interviews with artists Hannah deprived, Jonathan Woody, and scholar Susan McClary.

[01:00:52] Speaker D: You.

[01:01:07] Speaker A: Have you listened to Leydelisa's other podcast, music meditations.

[01:01:12] Speaker B: Music meditations combines poetry and music to bring soul soothing and life affirming art into your day. Featuring classic and contemporary poetry by Northeast.

[01:01:22] Speaker A: Ohio writers, along with curated performances from Les de Lisa's live performance archive, each bite sized episode concludes with prompts for mindfulness or guided listening to listen search.

[01:01:39] Speaker B: Music meditations wherever you found this podcast.

[01:01:52] Speaker A: Thanks so much for listening to this episode of Salon era. This episode was created by me, executive producer Deborah Nagy, associate producer Shelby Yaman, and Hannah Dipreste, our script writer and special projects manager. It originally aired in fall 2021 as part of Salanira's second season. Our featured guests were Metso soprano Raquel Winneka, young, violinist Karine Cuelarindon, and bassoonist Catalina Viquez Klein.

Support for Solanira comes from the National Endowment for the Arts, Cuyahoga arts and Culture, the Ohio Arts Council, and audience members like you. Solanira's season sponsors are Deborah Malamid, Tom and Marilyn McLaughlin, Greg Noson and Brandon Rood, and Joseph Sopko and Betsy McIntyre. This episode featured musical performances of music by Sarjuana Nestelacus, Rafael Castellanos, Antonio Duran de la Mota, and Andres Flores. A filmed version of this episode is available to salon Era members. Visit salonira.org and you can get full performance details, as well as learn more about the music and information shared in this and any episode. Please subscribe and leave a review on Apple Podcasts. It really helps the show.