Episode Transcript

[00:00:09] Debra Nagy: You're tuning into SalonEra, a series from Les Delices that brings together musicians from around the world to share music, stories, and scholarship with a global audience of early music lovers. I'm SalonEra executive producer Debra Nagy, and this is the first episode of our fourth season: Celestial Soundtrack. For this episode, we've invited violinist and SalonEra associate producer Shelby Yamin to guest curate this episode, in which we'll explore some connections between music and the cosmos.

Shelby has brought together some very special guests for this episode. Charlie Weaver is one of North America's finest loop players and a professor at the Juilliard School. He's also an expert on Renaissance music theory.

Juan Lora began playing the violin at age six and studied and performed seriously through college, but found himself fascinated by astronomy.

Today, he is a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Yale, where he researches planetary atmospheres with a particular interest in Titan, a moon of Saturn cellist. Leonie Adams joins us from her home in Slough, England, where she has been immersed in recording the musical works of astronomer William Herschel with her group, the Dionysus Ensemble.

Music and space might seem like strange bedfellows to us in the 21st century, but they were inextricably linked in the minds of theorists and composers throughout the Middle Ages, Renaissance and into the early modern period.

The ancient Roman philosopher Boethius believed that arithmetic and music together exemplified the fundamental principles of order and harmony in the universe. Such like concepts around the music of the spheres, from the ratios between frequencies that create musical intervals to alchemical thinking about order in the natural world, influenced theorists and musicians across the ages, from Pythagoras to Purcell to Mozart, Hindemith and countless others.

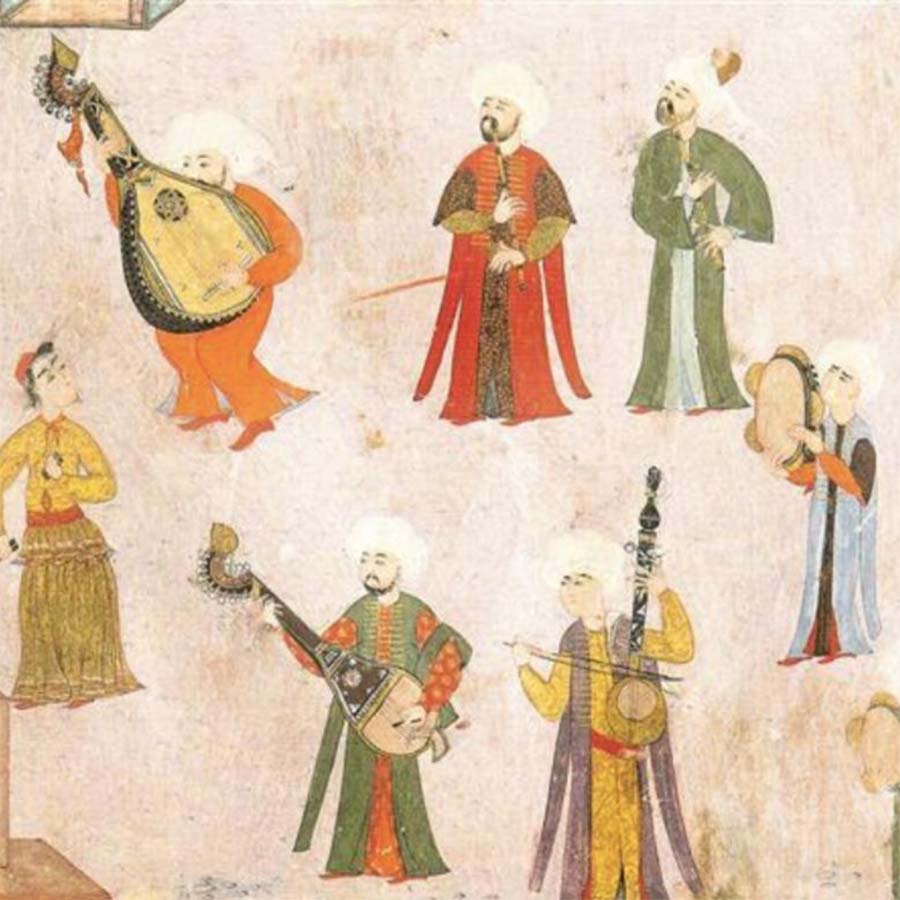

We'll even talk about several astronomer musicians in this episode. For one, Galileo Galilei, the late Renaissance scientist, inventor, and astronomer, played the loot, just like his father Vincenzo and his brother Michelangelo.

Not only did Galileo publish music, but his loop playing was said to have influenced or inspired some of his experiments, laying the groundwork for new theories and discoveries.

The 18th century astronomer and oboist and violinist William Herschel also came from a musical family, but gravitated towards science. He ultimately became the official court astronomer to King George II and settled in Slough, England, where, together with his sister Caroline, he built a 40 foot telescope that enabled his discovery of Uranus and infrared light.

Along the way, Shelby, Charlie, Juan and Leonie will consider current thinking and continued curiosity about sound and space. Over to you, Shelby.

[00:03:26] Shelby Yamin: Welcome, Charlie and Juan. It's so great to have you both here. Debra just gave us a little bit of an intro to this episode, and she touched on the concept of music and the spheres. But, Charlie, I was hoping you could lay a little bit of groundwork for us about this way of thinking.

[00:03:43] Charlie Weaver: Sure. Thanks for inviting me on to talk about this, one of my favorite subjects. So the idea of the music of the spheres has been very influential throughout the history of Western music, beginning with the ancient Greeks.

The idea seems to have first been formulated by the semi mythical philosopher Pythagoras, who was a philosopher in the sense of someone who studied the nature of being but also kind of a scientist, a mathematician, but also the kind of creator of this movement, this mystical movement of something like a combination of science and religion.

So in Pythagoras' view, the central feature of the universe is that it is made of number.

And in particular, the universe is an ordered place. It's a place of great beauty and natural order. And the order can be expressed as relationships between numbers. And when we expand this out to the cosmic realm, the different planets in this conception, the seven planets, including the Moon and the sun, sort of orbiting around the Earth in the older way of thinking about astronomy, these planets relate to each other in their distances in ways that are rational and express this sort of ordered cosmos. And it turns out that music is also made of number in a very similar way. So any combination of musical sounds can be expressed as a ratio. So the idea of the music of the spheres is that that proportionality between the planets that extends in this chain of being, between the Creator and humanity can be thought of as an ordered series of numbers. And as these planets are orbiting around the Earth, they're creating sounds. Because, of course, it stands to reason that anything moving so quickly must make a sound in the kind of ancient conception. And the sounds they produce must be a beautiful kind of cosmic symphony. And this idea gets passed down into the Western tradition primarily through the works of Plato and Cicero. And in Cicero's version, musicians on Earth are replicating the consonances that exist between the planets. And by doing so, they're able to achieve immortality and to ascend after this earthly life is over into this kind of cosmic realm. So there's this deep sense of resonance between the music we listen to the music of the planets and mediating between those two the music of the human body, which is the sort of middle microcosm between the things of heaven and the things of Earth. So Deborah mentioned in the introduction Boethius, who himself wrote this kind of great compilation of ancient Greek music theory. And his Boethius's book was the standard textbook on music theory right down until the 17th and 18th centuries. And in that book he expresses this connection between cosmic music, human music and the music of sounds.

[00:07:34] Shelby: In talking about how music and musicians were thinking about the connection to the cosmos and music of the spheres, was this a sentiment that was shared by scientific communities at the time?

[00:07:46] Juan Lora: Too absolutely, yeah.

So Charles mentioned Pythagoras, of course, but many of the Greek philosophers had conceptions of cosmology basically our place in the universe and how the universe is structured. And again, Charles mentioned the geocentric model, where Earth is in the center and everything else revolves around that, but that was taken quite literally. And observations of the sky, where you can see, for example, the sun rising and setting and the stars rising and setting, led to these conceptions of the universe as being set up with these spheres around the Earth. And these spheres had relationships to each other exactly as Charles was describing in these models. And these know, and the spheres would turn in different ways to explain basically the motion of the different things that we see in the sky, like the stars and the planets and all this. And it became a really complicated thing.

Aristotle, in particular, had this concept of uniform circular motion, I think is what he called. So basically everything that was heavenly was thought to be perfectly circular, perfectly spherical, and that sort of thing.

With these ideas.

Again, the model of cosmology at the time became increasingly complicated, but it always involved these sort of concentric spheres related to each other, in some cases, circles, and these things called epicycles, again, to explain what we observed in the universe, which is a very scientific way to approach things. But it was a worldview very much based around these cosmic spheres.

[00:09:47] Shelby: Well, you made the transition here pretty easy for me.

So in talking about observing these spheres and trying to make sense of things, we're going to jump forward quite a bit to Galileo. And in a minute, we'll hear Charlie play a piece by Michelangelo Galileo. But in the meantime, Charlie, could you introduce the first piece that we'll hear?

[00:10:11] Speaker C: The Galilee family was a rather large family of lutenists and composers and scholars of music.

The father of Galileo, Vincenzo Galilei, was himself rather well known as a music theorist. And Galileo himself also composed music and probably played the Loot, although we don't really have much of a record of that. But his brother Michelangelo was probably the best composer of the bunch, at least in my opinion. And he's writing music right at the beginning of the 17th century, a time of, of course, great discovery in science, but also a time of great stylistic change in music. So the tocchata that I'm going to play is a perfect example of this kind of abstract style of music. Prior to this time, most of what the Loot did was to play dance music, so people could dance or to accompany singing, or perhaps to play arrangements of pieces that had been conceived vocally.

But this new generation, around 1600, was interested in ways that music could express things without using words, without resorting to that kind of external purpose. And so the tocchata is a piece. It literally just means touched. It's something that you touch the instrument, and then out comes this music. And the music of this era is specifically designed to move the affect of the listener to create these kinds of resonance in the listener, similar to the resonance that exists between the heavens and the sounds of music. So by playing specific harmonies and Galile is quite adventurous in this regard some of the harmonies are quite dissonant and interesting. By using these harmonies, he's able to create a connection with the listener and create, hopefully, a mood that you listening to my performance will also feel so I'll be able to communicate through this abstract medium of music, which is itself very mathematical, to create kind of resonances with your emotional state.

[00:17:44] Shelby: Thank you, Charlie, for that beautiful performance. You mentioned that this Boethius text was used as the primary teaching source throughout this would be throughout the Galilee's education. And so how much of that Boethius mindset and text would have been considered in the Galilee family or in Michelangelo in his writing and in his, I guess, musical education?

[00:18:11] Charlie: I don't think we have enough information about Michelangelo to really know for certain. But certainly the idea of the music of the spheres well, I mean, a better example even than the Galilee family is Galileo's great contemporary astronomer Johannes Kepler, whose entire output of astronomical work is designed musically. Much of the motivation behind Kepler's discovery of the laws of planetary motion, which we still learn in physics class, was motivated by his search for the music of the spheres.

And by music of the spheres, he literally means proportions existing in some way in the planets. And the version that he sort of settles on in the end is that the real music of the spheres has to do with the ratio between the minimum and maximum speeds as each particular planet orbits. And altogether, these various ratios and changing speeds creates this kind of cosmic symphony that is perfect. So even though the Heliocentric model has replaced the geocentric one, that did not mean that the idea of cosmic proportion or its relationship to music had changed. And certainly the same must be true for the Galileo family. Galileo himself corresponded with Kepler. So many of these ideas, even within this family of kind of extreme empiricists and rationalists, would have continued to have great importance.

[00:19:59] Juan: Just building up on, again what Charles was just saying, especially about Kepler. He was motivated, basically, in continuation of the things we were discussing earlier from the ancients, basically, through the time that he was living, and so took incredibly precise astronomical measurements that allowed him to generate the laws of planetary motion, which again revealed that the orbits of the planets are not circular, right? They're elliptical. And that's what leads to these slight differences in speed. Again, he was really trying to understand how the motions of the planets relate to each other and in so doing, basically revolutionized astronomy. So it's a beautiful connection.

[00:20:52] Shelby: I'd love to talk now about the patriarch of the Galilee family, Vincenzo. My impression of Galileo's musical upbringing is that he was very involved in the experiments that his father was doing and very aware of all this experimentation, even though he himself didn't make a name for himself as a loop player. So I'm wondering if you can bring us into Vincenzo's work a little bit.

[00:21:16] Charlie: Sure. So Vincenzo seems to have shared Galileo's sort of cantankerous streak. But one kind of overarching theme of Vincenzo's theory is that he wants to replace the appeal to authority with a reliance on empirical observation. So one of the things about the music of the spheres is that it goes back to Pythagoras, who we've already spoken about. According to the old story, Pythagoras is walking along one day, probably contemplating the heavens or who knows whatever Pythagoras thought about. But he happens across a forge where a group of blacksmiths is smelting something. And he notices that the sounds produced by the hammers hitting the anvils are creating pleasant musical consonances. And so, according to the story, Pythagoras confiscates the hammers and runs a series of experiments on them and discovers that there's a proportionality between the weights of the hammers and the musical sounds that would be produced between them.

The problem with this experiment is that it doesn't work. You can't take a hammer that's twice as heavy as another hammer and just assume that it's going to make a sound an octave lower.

It works well for string lengths and it works well for organ pipes, but it does not work well for hammers. But this story had such kind of importance in the medieval mind that no one bothered to check it until Vincenzo came along and decided that there's actually not such a clear relationship.

And so he sort of turned the experiment into a different experiment involving weights on strings. So previously we had strings of different length and we talked about the relationship between them. Now, you have to imagine strings of the same length, but you're hanging different weights from the end of them. And according to the Pythagorean model, a weight that's twice as heavy as another weight should produce a pitch that's an octave lower. But when you actually run the experiment, as Vincenzo Galilei did, he discovered that you actually need a weight four times the weight of the other weight to create a sound and octave lower. That actually, the proportionality is not between weight and musical ratios, but between the weight and the square of the musical ratios, which, of course, is very similar to Galileo Galilei's discoveries about the laws of gravitation. So his Galileo observing this, it's very much in the theme of let's not rely on authority. Let's not take what scholastic writers of the Middle Ages had to say about really any physical phenomenon, whether it's dynamics or cosmology. Instead, let's rely on our own observation, which of course, is a foundational pillar of what we would consider the modern approach to science.

[00:24:50] Juan: His father's influence, just in the sense of being an empirically based thinker rather than someone who follows authority, was really critical. I mean, we talked about some interesting examples already, but a really famous one, of course, is that is his defense of the Copernican Heliocentric model, which got him in a huge amount of trouble. Right.

I think he lived under house arrest for a long time because it was against the teachings of the church at the time, but he basically stuck to it. And, of course, that was based on the empirical evidence at the time.

[00:25:30] Shelby: As we prepare to listen to this next piece, charlie, you mentioned earlier that Michelangelo was more forward thinking in his musical contributions. How does his music embody this approach that his brother showed in his astronomy and his father showed in his experiments with the strings?

[00:25:51] Charlie: Sure. Well, one aspect of the lute is that it can play multiple voices at one time, unlike an oboe or the violin, most of the time is just playing a single melody. And of course, the lute, like various keyboard instruments, is capable of playing multiple melodies at once.

And in the older model, in the 16th century, this is usually done by adapting pieces that were conceived as polyphonic vocal works and playing them on the Loot in that way of thinking. The lute is sort of like the 16th century version of the iPod.

If you want to hear a piece of music and you don't have, say, the resources to assemble a choir so that you can listen to it, one way that you can hear it is to arrange it for the lute and then play it for yourself. And that's Vincenzo wrote an entire book about how you go about doing that. Michelangelo, being in the next generation, is much more interested in using the texture of the lute in a more kind of creative way. So in this next piece we'll listen to, it's a dance piece, but it's not necessarily the kind of dance that you would dance along to. It's more just for listening or enjoyment in that way. But on the repeated sections of this piece, Michelangelo does interesting things with the capability of the lute to play different notes. So he creates this kind of texture in the music where the bass and the middle voices and the melody are kind of woven together in a way that is unique to the lute. And this style actually came to be called the lute style or the broken style. In French, we would say style brise.

And it was a real hallmark of the 17th century. And I think these dance pieces by Galilei are a fantastic early example of that style. So this is a dance of Volta, which is just basically an Italian dance of the period. Also from that same collection by Michelangelo, the book from 1620, where all of his compositions are gathered.

[00:30:08] Debra: Thanks for listening to today's episode of SalonEra guests curated by Shelby Yamin and featuring Juan Lora, Leonie Adams and Charlie Weaver.

Shelby has been SalonEra's associate producer since the series start and a frequent artistic collaborator. With your support, we can continue to collaborate with such engaging artists from across the country and around the world. You can support SalonEra by subscribing to this podcast and by donating at salonera.org your donations make every episode possible. Thanks again for supporting Les Delices and SalonEra by listening and subscribing to this podcast.

[00:30:55] Shelby: So we were just speaking about Galileo and how his musical life kind of influenced, possibly influenced his career as an astronomer. And now we are going to speak about another astronomer who had a musical background, William Herschel. And I'd like to welcome Leonie Adams. I'd love to ask you first, how did you become so involved in working with Herschel's music?

[00:31:18] Leonie Adams: Well, it's interesting. I live in Slough in the UK, and William Herschel is actually buried about three minutes walk from where I'm currently sitting.

His bicentenary was last year. He died on the 25 August 1822. And so there was a lot of excitement in the town about the upcoming Bicentenary and there was a lot of talk about what the town was going to do to celebrate this local legend. And somebody in 2021 mentioned to me, oh, well, of course, you know, who is a musician. And I sort of went, what? Really? Who? I don't know anything about this. And so I got really interested in what music he'd written and what was still out there and what hadn't made its way into the public domain. So I contacted the Herschel Society, who put me in touch with Alex Voice, who had photographed huge amounts of manuscripts, handwritten manuscripts of Herschel's, and I then asked him to typeset a few bits and pieces for us, which we've then recorded. So we did two harpsichord trio sonatas last year for the Bicentenary and this set of notionally twelve, (I'll talk about this in a minute) Solo Violin Sonatas although they're with cello, (I'll talk also about that in a minute), which have just been released this year, also on his anniversary as a celebration.

[00:32:51] Shelby: I know that Herschel has such a legacy as an astronomer in the scientific community. Is he also known as a musician or has that just kind of been overshadowed by his other accomplishments?

[00:33:05] Juan: I would say in the scientific community, of course, the astronomical community, it's been completely overshadowed. Again, if you dig a little bit, as we just heard, it's pretty obvious that he had quite an interesting career in music, but he just made so many huge contributions to astronomy. That's what we remember.

[00:33:23] Leonie: Of course, even in the musical community, he's known as an astronomer, he's not known as a musician. So this is new to vast swathes of the musical community too.

[00:33:35] Juan: He made so many incredible contributions, to be honest, it's an amazing thing to completely switch careers and do something like that. In a way, it's similar to what we were just discussing about Galileo in the sense that I think Empiricism really guided a lot of what he was interested in, and he was interested in a number of things that could only be done, really by even making his own tools. For mean, this is a famous example, of course, but he basically was making his own telescopes, and they were kind of an unusual type of telescope. So again, we talked earlier about Galileo, who's famous for having turned telescopes to the heavens. Right. Galileo was using refractory telescopes, meaning that basically they were telescopes with lenses.

Herschel used primarily, is famous for using reflecting telescopes. So these are telescopes with mirrors. And he basically came up with ways of polishing his own mirrors for the purpose of making his telescopes, which is really a fascinating thing. And of course, he made a bunch of other discoveries building his own tools, basically separating light, making little spectrographs with prisms, and then measuring things that way. So he was guided by the scientific interest, and he was really a MacGyver of sorts, to use a phrase.

So anyway, I don't know if that quite answers the question. It's, I guess, a polymath by any stretch of the imagination. He's really somebody who was interested in everything around him.

Yeah, we're lucky that he was.

[00:35:36] Shelby: So now we'll hear some music by Herschel. First, I'll play some excerpts from his collection of violin caprices. So these are caprices for solo violin, and they seem like they're more studies, like maybe etude type little works, but they're by no means easy. And one of the things that I was so struck by in learning these is that he's really exploring all the possibilities, whether they're easy or not. He has pieces in every single key, flats, sharps, and that's a rare thing to see in a collection of music for violin. Usually composers will choose to write in keys and in hand shapes and patterns that are really suited for the instrument. And I don't think that this is a mistake. I think Herschel was a violinist himself. It's not that he didn't know better. I think he was really just exploring all the possibilities, which it seems like is a kind of theme for him. Leonie, you were the one who told me that these caprices are in the same book as the violin cello duos.

[00:36:40] Leonie: They are. They're in a hardback bound volume, these and the ones we've just recorded. And what's really interesting is the set of twelve that we've just recorded, of which there are only eleven.

Number six is missing out of that book. The pages are simply missing. But the pages are I mean, they're not missing. They've been found elsewhere, but they're just not bound in the volume.

Number six is dated 1763, and they're on loose sheets. But if one presumes that he wrote number six in order, wrote one to five, and then number six in 1763 and then carried on. That gives us a starting point. Although you can't tell whether he wrote them all in one month flat or over the period of ten years, we just don't know.

He's quite slapped ash on his markings. I guess they were written for personal use rather than posterity.

[00:37:51] Shelby: Well, let's listen to some of those caprices, and then we'll come back and talk more about his compositions and your experience playing his music in your recent recordings.

[00:41:17] Ad for SE: Shipwreck!: Henry VIII's flagship, The Mary Rose, sank in 1545 with a chest full of instruments on board. Tune in on November 13 as we premiere Shipwreck, where we'll dig deep into reconstructing the sights and sounds aboard the Mary Rose. We'll talk with polymaths Alison Monroe and Peter Walker, who help tell the ship's story through music, alongside featured performances from medieval ensemble Trobar.

[00:42:07] Shelby: Welcome back, Leonie. When we were first chatting about your experience recording Herschel's chamber music, you mentioned to me this whole list of ways that Herschel seemed like he was experimenting, and I'm hoping you can share with our audience just a few of those that you encountered.

[00:42:24] Leonie: Sure. So this set of twelve, as I said, there were only eleven written.There are loads of anomalies, and each one seems like an exercise in something interesting that he wanted to explore.

You've called them violin and cello duos, which is how we've recorded them. But another interesting anomaly about these is that Herschel entitles them solo violin sonatas, but he then writes a bass line, and we had a lot of discussion about does this mean basso continuo with harpsichord or loot, for example, or does it simply mean a cello part? Basically, we didn't come to any kind of answer. Nobody could give any definitive answer.

It could have been just a mental harmonic guide for him to know where he was going with the music. I saw the bass line as a frame to the violin's picture, if that makes any sense at all, just to ground it a little bit in the harmony.

But it would be interesting to record them with harpsichord and hear the difference. Another conundrum that Herschel has presented us with many in this set. So, for example, the first sonata starts with a slow movement and then has two fast movements, but that's the only time he ever uses that format. He goes back to fast, slow, fast after that for the remainder of the set.

Number three is interesting because the last movement he explores theme and variations, with the violin part getting increasingly more complex and frenetic as it goes through.

Number five, I think number five is my favorite for being the most contrary. He brackets various of the violin notes and writes the word flagelletto over the top, which in itself isn't a desperately recognized term for harmonics, but he doesn't use any of the standard notation for harmonics. He doesn't use the diamond shape or the little circles. So the huge question mark is, does he want to hear the pitches of the notes he wrote, or because he was a violinist, is this a player's guide on where to find the harmonics, which obviously sound at a different pitch?

And my violinist, Robbie, felt very strongly that they were false harmonics, which were discovered in 1761, which fits with the theme of Herschel really grabbing onto new inventions and exploring them and pushing them. And I felt quite strongly that they were natural harmonics because there are various places where they echo the bass line and it seems to work musically for me, but usually with harmonics, what's going on around it, say, within an orchestra will give you the harmonic context of which notes should come out. But of course, these don't have that. So we've recorded them both ways, actually, and I'll be really interested for people to listen to both versions and see which they like best and see which they think he might have intended. But it's a huge question mark because he doesn't give us any definitive answers, either in the way he notates it or in any kind of instructions handwritten in the manuscript. There's just nothing there.

[00:45:48] Shelby: I should just say you have four albums of these violin duos, and because there's not a number six, as you mentioned before, number six is missing. So you actually do have twelve sonatas, but one of them is number five.

[00:46:04] Leonie: Absolutely.

[00:46:05] Shelby: Which I think is brilliant.

[00:46:07] Leonie: Yes, we perfectly completed what he set out to do.

[00:46:11] Shelby: So in addition to the four volumes of the violin and cello duos, you also have this album of his violin, cello and harpsichord pieces. And from what I understand, it's a set of three pieces, of which you recorded two. And I'm hoping you could share with our audience why that third one is saved for a future recording project.

[00:46:37] Leonie: Absolutely.

Again, this completely harks back to Herschel, exploring new technologies and really pushing the boundaries, because the sonata we didn't record is written for an instrument that we simply didn't know what it was and couldn't get hold of. There are various dynamic markings and various other markings within the score led us to believe that it was for a particularly bespoke, one off, almost exploratory type of harpsichord. It wasn't the harpsichord that became the standard recognized harpsichord, it was one of these sort of experimental models. So we're trying to track one down and we think there might be one in a museum somewhere that if we're allowed to get hold of it, we will certainly record this last sonata. But it doesn't fit the mold of what he's used in other harpsichord writing.

[00:47:36] Shelby: That's very cool. I really look forward to hearing that. So we're about to hear a piece from your recent recording. Can you introduce that for us, Leonie?

[00:47:45] Leonie: Sure we're going to hear the second movement from the Sonata number One in G Major, and it's an allegro, and you'll find it on volume three of our fourth set.

[00:49:40] Ad: Les Delices is celebrating the release of 2 CDs this November. If you're in Northeast Ohio, you can join us November 3 through five for several free and ticket events marking the release of The Highland Lassie, a Scottish Baroque program, and Noel Noel, a gorgeously recorded disc of holiday favorites. Or be sure to catch our upcoming podcast episode spotlighting the Highland Lassie that drops on November 27. Visit lesdelices.org for details.

[00:50:12] Shelby: Thank you all so much for being here today. This has been really fun to talk about these connections between music and astronomy. And even though we've been focusing on the past, the curiosity about music and space and sounds in space is definitely not over. Even as recently as 2021, the Perseverance rover captured sounds of wind on Mars. And this is something that it's just fascinating to people.

[00:50:39] Juan: Absolutely.

Sound, of course, is what we sense when a type of wave hits our ears, right? But there's many different types of waves in nature. And so the thing that NASA has done in addition to, of course, what you mentioned, Mars 2020, the Perseverance having literal microphones to listen to the atmosphere on Mars. What scientists have done with some NASA instruments is to take measurements of other types of waves or oscillations, and turn them into sound. And a specific one, which actually is a nice connection to everything we've been talking about because it comes from Voyager One and the Voyager spacecraft. Well, actually, it was Voyager Two. But the second Voyager was the only spacecraft ever to visit Uranus, which was the planet discovered by Herschel. So that's one, voyager One is an interstellar space, meaning it is now outside of the solar system.

And what they've done is taken measurements of basically the density of electrons in that space, which is obviously very low. But nevertheless, you can get a sense of how those electrons vary in space with electromagnetic oscillations, basically radio detections. And those oscillations are at frequencies that correspond to what we hear for sound, for sound waves.

It's a pretty straightforward translation to take those measurements and turn them into sounds. And they sound eerie, in a sense. You hear all these funny pitches that go up and down, and in a sense, that's the sound of space, even though, literally speaking, that's not a thing because space is mostly a vacuum. And so you don't have these pressure waves that are actually sounds.

Another nice, interesting connection is that Voyager spacecraft also detected, in a very similar way, detected signals that were turned into sounds around Jupiter of these things called whistlers, which we know from Earth.

Whistlers occur in Earth, and they're basically a response of the upper atmosphere to lightning. And so it turns out that Voyagers detected lightning on Jupiter. And so we can actually correlate those you know, in a sense, it's all connected. But I especially like the Voyager connection because it links everything we've been discussing together in a nice way.

[00:53:04] Shelby: And there's one more Voyager link to cover, which thank you for bringing us there. Not only where was the Voyager detecting sounds, but the Voyager brought some sounds from Earth on its mission. And so in the late 70s, when they were preparing this mission, Carl Sagan chaired this committee to send some sounds from Earth in with these spacecraft to wherever they end up. What's so beautiful to me is I've been reading about the process and about all the things that they considered putting on these records. And all the contributors had some really kind of profound things to say about why it was important to send music and how we're trying to communicate to, let's say, another. Some intelligent life form picks this up and wants to know about Earth. That music is really the thing that will communicate who we are as beings and the range of emotion and technical ability and things like that. It's so kind of validating for us as musicians for music to be acknowledged in that way. The last piece that we'll hear on the episode is a movement which was included in that Golden Record.

There were proponents, people advocating for the record to be mostly Bach or just include as much Bach as possible because that is what says the most about what we can do and who we are and the range of emotions. But they settled on included a lot of other things. But this one piece, this violin piece by Bach made it on there. So I will be playing that at the end of the episode.

[00:54:41] Leonie: I love the idea that there's an apocryphal story, which I hope is true, that you were talking about people advocating for a holy bark disc and that other people were saying no. That would seem like showing off, which I rather like that story. I hope it's true.

I mean, music is widely acknowledged to be the international language requiring no explanation, no learning or education of any kind, speaks across traditions, across seas, across ages, across preconceptions, across any kind of prejudice known or unknown. It just washes all of that away and speaks to us at the most basic of levels and drills straight into the emotion, almost bypassing the head, which is what I love, because then none of the rest of it that we get caught up with, especially at the moment, it seems none of that matters.

And you have a direct connection with somebody through music, and that's the only thing that matters, and it's a truth.

[00:55:59] Charlie: Well, for me, anyway, I think Leonie summed it up very beautifully.

I teach the idea of the musical spheres in my music theory classes. And when you ask me to sort of sum it up, I think, well, one obvious fact about the music of the spheres that Juan alluded to briefly, but we could maybe expand on, is that there is no sound in space, or at least there are no pressure waves that we would experience of sound. So why bother learning about the music of the spheres if it's just wrong?

And in defense of the idea, I would say that I think it's worth studying the music of the spheres not because I'm trying to convince anyone of a geocentric model of the solar system or anything like this, but because the idea of order, sympathy between different ways of hearing or sensing. So the kind of wonder that humans just sort of naturally feel when confronted with the cosmos and the wonder that we naturally feel when we're confronted with music, these things have deep connections. They have had deep connections for many scientists throughout the history of science. Not only Galileo and Kepler, but also people like Newton and Euler wrote about music theory and had interesting things to say about music theory. And we often think of music and science as being very different branches of knowledge, but in the Pythagorean view, they were much more intricately linked. And I think there's some interesting inspiration that we might draw from that, both as musicians, but also as just sort of modern people or perhaps even as scientists.

[00:58:17] Juan: Yeah, I completely agree.

Speaking specifically about the Golden Records, there's many things about that that are really beautiful. But in addition to music and language, I think part of the idea was to tell a story about Earth, right? And so there's sounds not just animals, but natural sounds recorded for some future civilization to listen to, perhaps. But the intention is, again, to tell the story of Earth and then to tell the story of humanity. And of course, the fact that music is that story, I think, says a lot in the sense that music is sort of the culmination of human achievement, or one of the culminations of human achievement alongside science and astronomy, of course, is sort of emblematic of that. And that relates very closely, of course, to what Charles was just saying.

Both music and astronomy are these disciplines that, at their core, have awe of the universe and a desire to understand it. Both of these disciplines really display the best of humanity.

And we did really well, I think, with Carl Sagan leading it's not a huge surprise, but we did really well in sending that as sort of the emissary of humanity into interstellar space.

[01:03:13] Ad: Have you listened to Les Delices' other Podcast, Music Meditations? Music Meditations combines poetry and music to bring soul soothing and life affirming art into your day. Featuring classic and contemporary poetry by Northeast Ohio writers, along with curated performances from Les de Lisa's Live Performance Archive, each bite sized episode concludes with prompts for mindfulness or guided listening to listen. Search Music Meditations wherever you found this podcast.

Thanks so much for listening to this episode of SalonEra This episode was created by me, Executive Producer Debra Nagy, Associate Producer and Guest Curator Shelby Yamin and Hannah De Priest, our script writer and special projects manager. Our guests were lutenist Charlie weaver, scientist Juan Laura and cellist Leonie Adams.

Support for SalonEra is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, Cuyahoga Arts and Culture, the Ohio Arts Council, and audience members like you.

Special thanks to Michael and Wendy Yamin and an anonymous donor for their sponsorship of this episode, to Robert Morris and Patricia Hanley, for their sponsorship of artists Shelby Yamin and to SalonEra's season sponsors Deborah Malamud, Tom and Marilyn McLaughlin, Greg Nosan and Brandon Ruud and Joseph Sopko and Betsy McIntyre.

This episode featured musical performances by Shelby Yamin, Charlie Weaver and the UK based Dionysus Ensemble of works by Michelangelo Galilei, William Herschel and Johann Sebastian Bach. A 1 hour filmed version of this episode is available SalonEra.org where you can also get full performance details and learn more about the music and information shared in this and any episode.

Please subscribe and leave a review on Apple podcasts. It really helps the show.