[00:00:05] Speaker A: This is Deborah Nagy welcoming you to Musical Vision, the first episode in Solanira's 202526 season.

Since 2020, Solanira has premiered over 50 episodes, each of which features a slate of national and international artists sharing live performances, pre recorded content and intriguing conversation you won't hear anywhere else.

In this episode we'll consider the legacies of blind and visually impaired historical performers and composers and talk about contemporary blind musicians experiences.

We'll talk with and hear performances by vision impaired harpsichordist and violinist Albano Barberi. Lutenist Lucas Harris will preview an upcoming recording of works by Giacomo Corzanis and Braille music Engraver Kathleen Cantrell will talk about her professional journey enabling score access and music literacy for the blind community.

But first, let's enjoy a recording of Engels Nachtigeltche or the English Nightingale by Jakob von Eyck. He was one of the best known musicians in 17th century Holland where he worked as a carillon player and technician, a recorder virtuoso and a composer.

He is known for his collection of 143 compositions for the recorder collected in Der Flauten Lustros, many of which feature increasingly ornate variations on well known tunes that display Van Eyck's ingenuity, imagination, imagination and prodigious technique.

Van Eyck's English Nightingale is performed here by Catherine Montoya in a recording made for Solanira in 2021.

[00:01:57] Speaker B: SA SA SAM IT SA.

[00:05:31] Speaker C: Welcome Lucas, we just heard a piece by Jakob van Eyck from 17th century Holland who was also a blind musician, and I know that you have been doing quite a bit of research and making concert programs that highlight the history of vision impaired musicians and I'm wondering how you came to develop this particular interest.

[00:05:59] Speaker D: Well, in addition to being a lutenist, I'm also a choir director and my choir has a tradition of doing these concerts. We call them Cafe Musiks. There's coffee involved, but they combine music with narration and I like to use these Cafe Musik formatted concerts in order to look at music history through a particular lens. A few years ago I hit upon the idea of a concert that would feature blind musicians and composers and it turned out to be one of the most fascinating projects I've ever done. I've since done a couple of lectures on the topic of blind musicians and I also discovered that blind musicians played a significant role in the evolution of my own instrument, the lute. And I'm actually planning to do a recording later this year of music by blind lutenists who were some kind of.

[00:06:49] Speaker C: Notable figures or composers that you know outside of music for the lute that. That you brought to light there.

[00:06:57] Speaker D: So for that particular program, we started with. It was. It was chronological. So it started with the Renaissance and went all the way to the present day. And we premiered a new piece by a blind composer and pianist who accompanied us at the piano.

So we started with Antonio de Caboton, the Spanish keyboard player, A lute song by a composer called Arnold Schlick. We featured harp music by O. Carolen. There was a segment about Bach and Handel, actually, because some people don't know that both Bach and Handel went blind at the end of their lives.

And there's a very interesting story about how they were both operated on by the same charlatan eye surgeon called John Taylor. So we told that. That whole story in the narration.

And we did music by Maria Theresia von Paradis.

We did choral music by George Alexander McFarren, a piece by the young Joachim Rodrigo. Oh, and of course, Louis Viern, the French organist. And one of the really fun things about this concert is that I figured out why there are so many blind French organists. France had been kind of de Christianized during the French Revolution, right? So when the Catholic church was kind of trying to find its feet again in the early, earlier part of the 19th century, there were no organists around, or very few. And there were very few organ students.

And they were trying to get up, you know, get Catholic church services going again.

And they ended up training blind students from this French National Institute of the Blind, which is still in operation to this day. There was an organist who began to give free lessons to the blind students there.

[00:08:43] Speaker B: And.

[00:08:43] Speaker D: And the program kind of built itself up so that eventually they had a five manual organ there, and they had a whole bunch of organ students, and they started to send out these blind students to play at these Catholic Church services.

And the whole system kind of kept evolving to the point where it was a very common path to do kind of an initial organ study there and then go to the conservatory. And there were a number of blind students in that conservatory. And one last thing about that story, a very important figure in that story is Louis Braille, the inventor of braille, who was actually a student at the institute at the time and invented braille when he was 15 years old and also made a musical version of braille to help these organ students cope with the amount of liturgical music that they needed to learn to get through kind of a year's worth of Catholic services.

[00:09:40] Speaker C: That is fascinating. And we're Going to talk with Kathleen later on in this episode about braille music and notation.

[00:09:50] Speaker A: Of course.

[00:09:51] Speaker C: We'll talk with Albano in a few minutes, also about his musical practice and how vision impaired artists collaborate.

But tell us in the meantime a little bit more about the work that you've been doing on blind luteness and the way that music for the lute is notated.

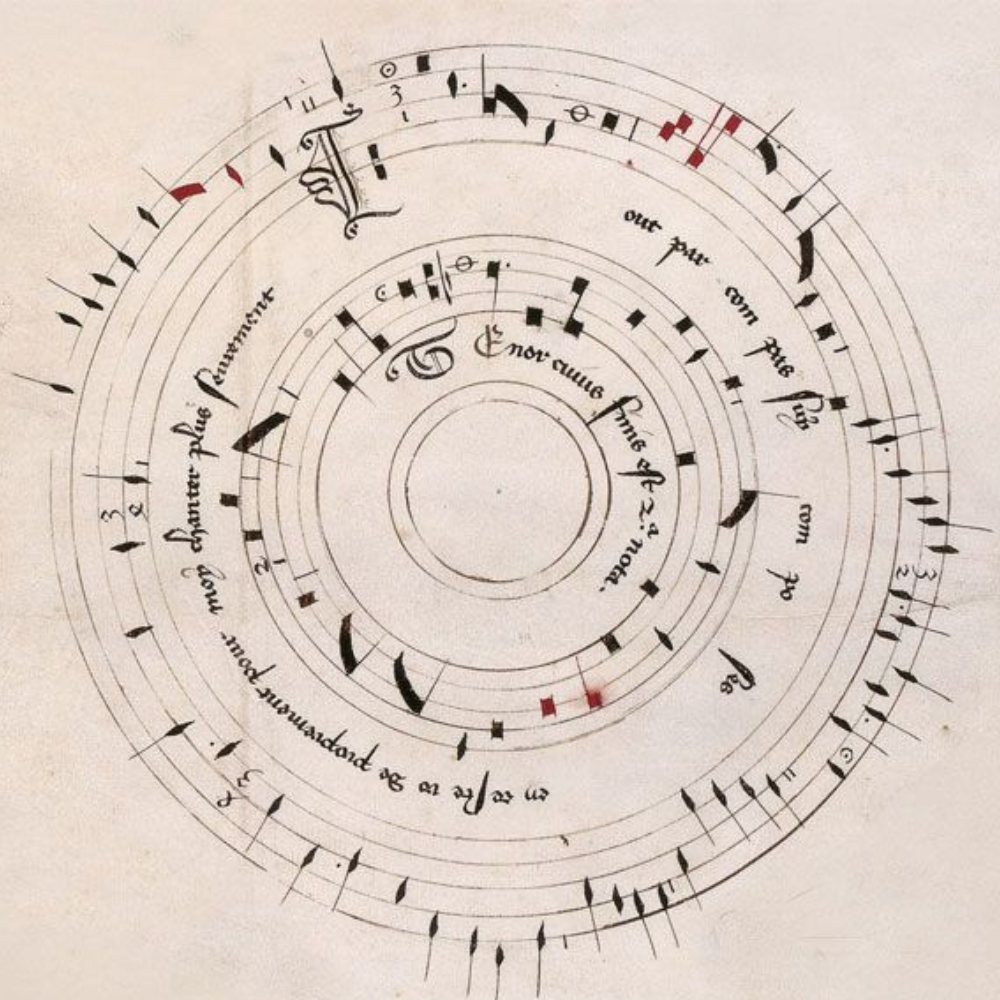

[00:10:07] Speaker D: There was a figure called Konrad Pauman. Conrad Palman was a German organist lutenist. He may have been the one who invented lute tablature.

His lute had five courses of strings and seven frets. He gave a different symbol to every kind of note location on the fretboard. And that might have functioned as almost kind of a proto braille music notation.

I should also add that Pauman may have been really the person who started to play polyphony on the lute because he lived at a time where the lute made a huge transition from being a plectrum instrument that had no frets to being more of a polyphonic instrument where the players added frets to the neck and then dropped the plectrum and started to play with their fingers. And he may actually have been the one who started doing that.

But then the next lutenist was this guy, Arnold Schlick, who was the first German.

He was also a keyboard player and lutenist. He published the first real lute music and the first lute songs in a book that has both keyboard music and lute music. And he may have studied with Pauman. And so, you know, I'm. I've kind of come to realize that this whole kind of beginning of polyphony on the lute may have been started by these blind kind of lute keyboard composers in Germany.

[00:11:36] Speaker C: Fascinating.

Well, we're going to hear lute music by Giacomo Gorzanis. And can you talk to us about the suite that you've recorded?

[00:11:45] Speaker D: Yeah. So Gorzanis was.

He lived in kind of the mid 16th century. He was from Puglia in the south of Italy.

He became a citizen of Trieste in 1567. And he describes himself as being blind in his publications. We think he was probably blind from birth.

One thing that's interesting about blind composers is that many times they work with what's called an amanuensis, which is like a secretary. It's somebody that kind of can help them write down their music.

And sometimes in some cases, we know who that person was with Gorzani's. It may have been his son who published Garzani's final loot book. In 1579. And he, he says he had collected the quote, the few fruits of long study, composed by my father of blessed memory.

There are two reasons why Gorzani's music is not known better. One is that it's full of really virtuosic diminutions.

He would be what they would call in the heavy metal world a shredder. He just like, he clearly had like a technique for fast passage work that's much better than mine.

And the second reason is that the music is full of mistakes, so requires some correcting.

But the suite begins with a dance piece. It's called Saltarello d' eto lzorzi, which is in two parts. And then I wanted to feature one of his polyphonic pieces. So you'll hear I reach your car.

And then I'll finish with a passamezzo that's called Passemazzo della Rocco fuzzo. And then finally a Paduana, which is a companion piece to that Passem.

[00:17:55] Speaker B: It Sam.

It it.

Sam.

[00:21:58] Speaker C: Lucas, thank you again for that beautiful performance and sharing a bit of the music of Gorzanis with us. I'm pleased now to have Albano join us. And I understand that you guys are old friends. How did you meet and get to know each other?

[00:22:14] Speaker D: Well, we met through a wonderful woman who is now Albano's wife. They invited me over to their apartment one day and we had a wonderful dinner and played lutes and harpsichords and fiddles and nickel harpas and we had a wonderful time. And that was the first time I met Albano. And since I've. I've gotten to know Albano a little bit through his amazing YouTube channel as well.

So I'm really, really happy that he's here to chat with us. You know, one of the perspectives I'm missing, of course, as a researcher of some of these blind composers, is the perspective of a current blind musician who understand things about this that I will never understand.

[00:22:58] Speaker C: Fantastic. Well, Albano, welcome. Lucas just rattled off a long list of instruments.

Can you tell us what instruments and music you are most engaged and fascinated by?

[00:23:11] Speaker E: My sort of bread and butter of music that I'm most interested in is music of the French Baroque.

I'd like to say that in general, I'd be happy to play music of the 17th through the early 19th centuries.

I play various types of harpsichords.

I am also a baroque and modern violinist.

And recently, as in the last few years, I have also developed an interest in Scandinavian and specifically Swedish folk music by means of an instrument known as the Nikkoharpa. So. So, yeah, I guess I'm sort of broadening my musical interests a little bit with that one.

[00:24:04] Speaker C: How did you get into this super specialized area in early music?

[00:24:08] Speaker E: So I started playing violin when I was five.

One of my favorite tapes I had as a child was a recording of Bach's Brandenburg Concerti.

And one of the concerti is the fifth one, which includes a massive solo harpsichord interlude, I guess, including a very iconic cadenza.

Actually, I guess that whole interlude is a cadenza in itself. But anyways, I heard this one day when I was 9, and I had never heard a harpsichord before. So I was very fascinated by this. And I asked my violin teacher what this was, and she said, oh, it's this ancient kind of plucked piano. No one plays it anymore. And I said, well, someone must be playing this because I just found this recording.

And then a couple years later, when my family moved to the States from Greece, I met another blind musician, early musician, singer named Maria Giorgacaraku, who Lucas also knows incidentally.

And she sort of opened my eyes to the whole concept of historical performance in early music, and I was smitten.

[00:25:38] Speaker C: Well, we're going to hear a little bit of your artistry. A Unmeasured Prelude by Louis Couperin, and you're playing on a very unusual instrument.

[00:25:50] Speaker E: Yes. So this. The instrument in this recording is known as a keyed lyre. And I describe it as a modern instrument inspired by a historical precedent.

In the late 16th century, there was a form of this instrument known as a clavisotherium, which was often an upright instrument where the body of the instrument pointed, was vertically oriented, with the keyboard sort of projecting from the front.

And these instruments were often strung in gut as opposed to metal.

And so Stephen Sorley, the maker of Mikey Dyer, actually makes versions of these clevis etheria.

And this keyed lyre is basically a horizontal version of a clavis etherium. It is essentially just a frame with partial soundboards strung in synthetic gut, fluorocarbon strings, but otherwise played very similarly to a harpsichord. It has a plucking action like a harpsichord does, but as you can hear, the sound is very different, much warmer, less metallic, and sort of evocative of a marriage of sound between a harp and a theorbo or a lute.

[00:27:22] Speaker C: I find it very compelling and very beautiful. And let's take a moment now and listen to this prelude.

[00:27:31] Speaker E: So this one is one of two unmeasured preludes in F by Louis Couprin. I describe this one as the bigger.

[00:27:39] Speaker C: One Fabulous let's listen SA.

[00:31:46] Speaker F: Thanks for.

[00:31:46] Speaker A: Listening to today's episode of Solanira, which features recent recordings by our guests harpsichordist Albano Barberry and Luteinous Lucas Harris, plus recordings of music by blind composers Joaquin Manuel Da Camara and Jakob Van Eyck from the Solanira archives.

Solanira is available in two formats as a video web series on YouTube and at Solanira.org and as an audio podcast. All video episodes from season six stream free on YouTube and at Solanira dot org from their premiere through June 30th 30th and audio podcast episodes are available anytime on our website or wherever you listen to podcasts. Podcast listeners can also access exclusive audio only episodes about the creation of Les DeLisa's concert series programs that include musical insights, historical context and audio highlights.

In a moment we'll introduce Braille music engraver Kathleen Cantrell and return to our comic conversation with Lucas and Albano. But in the meantime, I hope you'll consider making a tax deductible gift in support of Solanira. With your support, we can continue to collaborate with engaging guests from across the country and around the world.

You can support Salanira by subscribing to this podcast and by

[email protected].

support your donations make every episode possible.

Thanks again for supporting Les Delices and Solanira by listening and subscribing to this podcast.

[00:33:34] Speaker C: Welcome back and I'm pleased to introduce Kathleen Cantrell. Kathleen, we have known each other for many years, actually going back to graduate school, and I've been following your work, which has gone in directions that I didn't expect and perhaps you did not either.

[00:33:51] Speaker G: It has definitely gone in a different direction than I ever planned as well. I have two degrees in music and what I expected my life to be was teaching at a university, having private students, performing, and I did all of those things and it was less fulfilling than I expected it to be.

I ended up back in graduate school for library science and I was living in Louisville, Kentucky at the time, and that is where the American Printing House for the Blind is and I got a job there. And while I was there I learned about Braille music and I was shocked that I had never heard about it because I'm a trained musician. That's what I've been doing all my life and it was fascinating to me, but also I realized that there was a huge need for it. So I decided to try my hand at it and see what it was about.

And now I have this career that it keeps me so busy, but it is so fulfilling, and it's such a wonderful. A wonderful path that my life has taken.

[00:35:00] Speaker C: So you are a leading transcriber and also teacher of the engraving of braille music.

Can you tell us a little bit about the history and background and how it works?

[00:35:13] Speaker G: Sure. Lucas actually started this conversation off really well because Louis Braille himself was a cellist and an organist.

And, you know, it's kind of appropriate that we're talking about this right now, because this is the 200th anniversary of the completion of the braille system. Louis Braille sort of finished his six dot version in 1824, 25, and just a couple years after that, in 1829, he finished the music Braille code. And so not many people know that it was developed right next to the literary code because he knew how important it was for musicians to be able to read music.

And so over the years, over the last 200 years, there have been adjustments and additions, but by and large, it's the same system that Braille himself developed.

Music Braille in a nutshell, it uses the same six dots that literary braille uses.

And in one cell of those six dots, you get the top four dots give you the name of the note, whether it's a C or a D or an E. And the bottom two dots, the configuration of those will tell you the note value.

And then basically, it kind of reads like a story. It's very. It's horizontal. It's not a vertical alignment like print music is.

But there will be symbols and signs that come before the note that tell you how to play the note, the articulation, which octave you're playing in, and then you'll get to the note. And then things that come after the note will tell you how to end the note, whether it's the end of a decrescendo or. Or a fermata or a breath mark. And so you'll get that information afterwards.

[00:37:07] Speaker C: What is the biggest transcription project that you've been involved in? What are you transcribing on a daily basis?

[00:37:13] Speaker G: I mean, the biggest project that I've ever been a part of was the Norton Anthology of western music, all three volumes from medieval all the way to the 20th century, 21st century. That felt like a really big, really important project.

However, every single project I do, I feel like, is really important. Whether it's a clarinet part for a middle school band student or a cello part for the professional cellist that I transcribed for in Pennsylvania, or the Student that I transcribed for at Eastman School of Music.

[00:37:52] Speaker C: What are the system's limitations, if you feel that there are any.

[00:37:57] Speaker G: The tablature system is not able to be represented with the braille music system.

However, there are people, there's a colleague of mine who just came up with a new code that can actually handle and transcribe tablature in a very concise, very interesting way.

So that was really exciting to have that happen. But for standard notation, there really isn't much that we can't show in braille music.

I think the only, you know, performance limitation would be that you have to use a hand to read the braille. So reading and playing at the same time is difficult for most musicians. But braille music readers are really great at memorizing. So there's a lot of memorization shortcuts that we can use to help them memorize the music very quickly. I do a lot of full score transcription for college students. And for conductors with a full score braille transcription, it's usually one measure per page. So it's, you know, reading along with the recording in real time is challenging.

[00:39:14] Speaker E: That last point is one that I have come across many times. And I would argue that that is actually one of the. The greatest challenges, not only to braille music, but braille as a whole.

It is very large just by its, its nature. If you have it any smaller, it would not be perceptible, I would, I would say, or perceivable tactically.

And so when you have situations where you have one measure per page, be it a score or be it a particularly elaborate keyboard transcription, that's when you know you need the time. And oftentimes the musical world doesn't give you a whole lot of time. So, you know, it's.

It's a great challenge.

[00:40:20] Speaker H: In a moment, we'll feature a Modinha or song by Joachim Manuel da Camara called Desde Odilla. Da Camara was born in Rio de Janeiro in the late 18th century.

He was a blind, mixed race guitarist who learned music entirely by ear.

He was part of the oral tradition and he composed his own songs as well.

Besides these few facts, we know almost nothing about him. His beautiful compositions would also have been lost to us if they had not been heard and transcribed by an Austrian visitor to Brazil named Sigismund Neukom.

Other traveling Europeans heard Joachim's playing and wrote about his incredible talent.

One French prime minister, Charles Louis de Sausse de freycinet, wrote in 1817, nothing seemed to me more astonishing than the rare talent on guitar of Joachim Manuel.

[00:41:13] Speaker A: Under his fingers the instrument had an.

[00:41:16] Speaker H: Inexpressible charm that never more have I found among our most eminent European guitarists. When Joachim Manuel's music was written down by Neukom and published some years later in France, Neukomm wrote out forte piano parts to accompany the songs. We can only imagine what Decamara's own accompaniments on the guitar might have sounded like. Certainly they must have been unique and beautiful to have been called out for their quote, inexpressible charm, the likes of which were not matched by the best European guitarists.

This performance of Da Camara's Desdeodilla was recorded for Salon Era in 2021 by soprano Danielle Reuter Hera and Henry Lebedinsky playing on a late 18th century square piano.

[00:43:24] Speaker C: SA welcome back everyone. Albano I wondered how you learn new music.

[00:44:51] Speaker E: Sure.

So I discovered fairly early on that the most effective method of learning music for me personally is by ear.

I am able to listen to a piece of and fairly quickly memorize a lot of detail.

What I tend to do procedurally is listen to the piece several times over from different recordings.

And what that does is it kind of paints the general picture of the music in my head.

It teaches my brain what to expect so that then when I start listening to smaller segments of the piece, I can almost do the equivalent of predictive text input.

And depending on the complexity, it can take as little as a couple of days or as much as a couple of weeks.

It also varies depending on what type of instrument the music is written for.

A violin piece will be much faster and easier to learn because it is generally a single line multi voice fugue will take longer.

[00:46:18] Speaker C: Do you ever refer to a score?

[00:46:21] Speaker E: I am pretty good at getting a lot of detail from the recordings.

Part of the challenge I have is that Braille music, especially for earlier music, in my experience, has been harder to obtain.

I can go I have access to the National Library Service, web Rail or Bard interface since I am still a U.S. citizen. So I can jump on there and find a fair bit of music for pieces like say, Bach's keyboard works.

But when we're talking about Louis Couprin Preludes or Danglebert Suites, that's when I start running into more challenges in obtaining music.

So given the fact that I often have to learn music fairly quickly, I find it easier to just not worry about the score and just jump in with a recording. The other thing to keep in mind too is that at this point in my musical career I have my own sort of musical voice and ideas.

So no matter what I learn from, sooner or later I will make it my own.

But by having a number of different recordings, when possible, that bias is minimized. I wouldn't say eliminated, but minimized.

[00:47:57] Speaker C: I would love to also open the conversation up to sources. Let's just call them as historical performance folks who are cited and who are kind of obsessed with original sources and what is in the notation and what we're meant supposed to understand about, you know, the what, what's not written but it's part of practice. Like it's so interesting and so complicated and braille being actually 200 years old also as a technology and there are all these other new technologies, you know, never mind audio recordings, but e texts and other sorts of audio transcriptions. And I'd be curious for, for how those have, have changed your work and life.

[00:48:41] Speaker E: We're talking about eText for example, and there are devices out there, but ultimately it still comes down to the same braille code, right?

And also with these devices, until fairly recently, refreshable braille displays consisted of a single line of refreshable braille cells.

But what if you have to read multiple lines of braille simultaneously? Like if you're trying to read a left hand part and a right hand part, you can't really do that with a single line braille display. Now you have companies producing multi line braille displays which aim to change that picture a little bit.

But of course the challenge in this is affordability.

So yeah, that's, it's a series of challenges, but it's also sort of a cause for optimism because there's obviously work being done to make music more accessible in an electronic form.

[00:50:03] Speaker D: In my research I went into it with this idea that I was kind of saying, wow, isn't it amazing that all of these blind musicians succeeded and composed and did all these things in spite of their blindness?

And pretty quickly I sort of changed that attitude completely. And I started to think maybe their blindness was actually an asset or a gift.

In a funny way, I discovered that in many cultures, blind children are actually encouraged to go into music.

And it makes sense because they're less suitative to physical manual labor. But it seemed at the time, and I think maybe still to this day in some places, that music is a great thing for blind children to get into.

The blind journalist that I worked with in my project, who was our narrator, said that serial memory techniques become a very important substitute for visual cues.

And so basically blind people have a special gift and develop the skill for committing things to memory in the right order, which turns out to be a huge, really important thing for music. I just wanted to throw that out there because I don't want people, the viewers, to kind of come come across with the impression that it was impossible for blind people to engage in music before all these technologies were there. Obviously like way back in the medieval period, in the Renaissance, in non western cultures, there's massive amounts of evidence that blind people are some of the most skilled musicians in society.

And I really finished by thinking, you know, that initial attitude of wow, they succeeded in spite of their blindness was really not the right way to look at it. It was more like their blindness actually sort of provided a bridge to music that gave them certain skills that sighted people didn't have.

[00:52:16] Speaker E: You're absolutely right. Actually, it is very important to keep in mind that no matter the technological advances, a blind musician's best friend and most valuable tool is always memory.

Because unless you're a singer, you know, even if you have access to braille music, as Kathleen was saying, generally speaking, instrumentalists cannot read and play at the same time.

So memory is paramount. And there's also another sort of advantage to memorizing things, which is that you truly make music your own. Not only the particular score or piece that you're working on, but the style and the type of music is something that you become very intimately familiar with and can therefore improvise with and tweak and adjust and really play with and make new all very dynamically.

[00:53:30] Speaker C: Thank you so much for being a part of this conversation. Thank you so much for the beautiful performances that have been been contributed. I'd love to wrap up this episode with one final performance by Albano. And this is a performance of Claude Balbatre's character piece La Dricour.

It's a really beautiful and rich piece that features the low register of the harpsichord. And there are a variety of ways, Albano, that you, in addition to interpretation, have made this piece your own.

[00:54:06] Speaker E: There were a number of both stylistic and I guess, technical choices that I made with this recording. One of the most telling musically I think for this piece in particular, is my use of time dilation and contraction, which allows the music to breathe and also allows the instrument to.

To breathe. Different instruments sort of have pitches where the frame and the soundboard tend to resonate at their best. And the strings too. And in this harpsichords case, the pitch is right around 404, 405 hertz. This is a temperament I sort of settled on after playing around with the sound of my instrument. And so I think all of that plus the very rich bass resonance on that instrument just results in very, very rich and complex sound. So I hope you enjoy the performance.

[00:55:11] Speaker D: Can't wait to hear this.

[00:55:12] Speaker C: Fabulous. Thank you again for joining us. Let's enjoy Balbatre la Terricor.

[00:59:23] Speaker E: She's a.

[00:59:23] Speaker D: Nigher nor vessel a vessel of fame.

[00:59:27] Speaker E: She hails from a swago and the Twilight's her name.

[00:59:30] Speaker F: Tune in on December 15 for music.

[00:59:33] Speaker A: And labor from Ceylon era.

[00:59:35] Speaker H: Together with conductor Anthony Tresek King and ethnomusicologist Gib Schwartz Ruffler Solanira probes the.

[00:59:42] Speaker A: History and evolution of sea shanties and.

[00:59:45] Speaker H: Related work songs from the 18th to the 20th centuries, featuring live concert recordings by Sean Daggerwood, Les Delis and much more.

[01:00:06] Speaker B: Foreign.

[01:00:12] Speaker F: Thanks so much for listening to this episode of Salon Era. This episode was created by ME Executive Producer Deborah Nagy, Associate Producer Shelby Yaman and Hannah DePriest, our script writer and Special Projects manager. Our guests were Albano Bearberry, Lucas Harris and Kathleen Cantrell. Featured performances were provided by Lucy Lucas Harris and Albano Berberi, in addition to Salon Era Archive performances of music by Jakob Van Eyck and Joaquin Manuel da Camara performed by Catherine Montoya, Danielle Reuter Hara and Henry Lebedinsky, respectively.

Support for Solanira is provided by Cuyahoga Arts and Culture, the Ohio Arts Council and audience members like you.

Special thanks to Mark Vincent and Alex Nalbach who sponsored this episode episode of Solanira in honor of Jackson Douglas and a huge thank you to Solaniera season sponsors Deborah Malamud, Tom and Marilyn McLaughlin and Greg Nosen and Brandon Rood. A one hour filmed version of this episode is available on salon era.org where you can also get full performance details and learn more about the music and information shared in this and any episode. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. Consider making a donation@salon era.org and submit a review. It really helps the show.